Imagined and reimagined. Made and remade. The story of Dracula, first created by Abraham Stoker in his 1897 novel of the same name, has been interpreted on film as much or more than any other literary work, save perhaps for ‘A Christmas Tale’. What makes this story so enduringly powerful, and why is it that so many filmmakers have seen fit to apply their own thoughts and ideas upon it? Perhaps it is the simple notion that Dracula is at once terrifying and seductive, powerful and intimate. He threatens his victims with the gift and curse of eternal life. He stands as a paradox, then, of pain and pleasure, fear and joy.

This paradox has made its way to film; some versions downplay the seduction while others revel in the mysticism and magic. The film versions of Dracula all have similar threads but manage to be remarkably dissimilar experiences, and that’s not even counting the hundreds of vampire movies that have nothing to do with the original story in any way. Let’s set those aside for now, though. Let’s take a moment to look at the four most famous renditions of Dracula, spanning nearly a century of filmmaking.

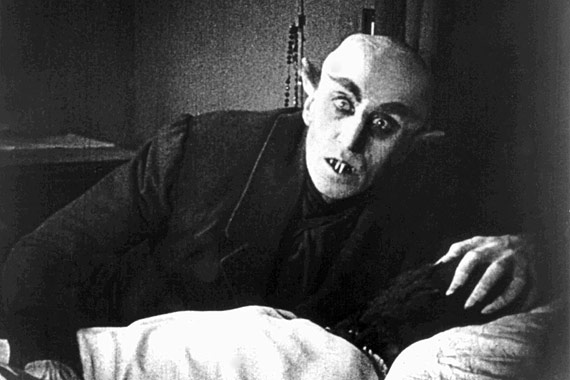

Nosferatu [1922] – Directed by F.W. Murnau

It is not a simple contrivance to say that this first take on Dracula, Murnau’s ‘Nosferatu’, is the very best. One of the most enduring of all silent films, and perhaps one of the best films of all time, ‘Nosferatu’ stands as a remarkable work that manages to instil unease in the viewer, even today. Many casual viewers are likely to cast the film aside as a novelty, a relic of filmmaking past. It is their loss to do so.

At the heart of the film is its interpretation of the Dracula character. Here named Count Orlok as a result of licensing issues involving the original Dracula text, he is as much a feral, dour creature as he is recognizably human. Buoyed by an inspiring performance by Max Schreck, Orlok is a frail, wispy figure. His nails are freakishly long. His two front teeth are fangs, not even bothering to hide inside his mouth. His bald head and pointed ears recall nothing less than a twisted, demonic elf. The first reveal of his image, a castle door slowly opening in front of him, is as classic and haunting an image as can be found on film.

Cinematographic tricks are used throughout the film, harsh shadows and unnatural body movement frequently used to illustrate Orlok’s otherworldly presence. There are some shots which people who haven’t even seen the film will likely recognize; a hideous shadow floating through a hallway, the vampire rising magically from a coffin. It’s a relentlessly beautiful film, and recent restoration efforts have ensured that the print is in beautiful shape, especially considering its age.

The original novel’s connection to the Black Plague is clearly in evidence, with plague rats playing a crucial part of the tale. Anne Rice saw fit to include rats in her own ‘Interview with the Vampire’ in a nod to the original tale. Despite what must have been a small budget, the film gets much mileage from its cramped interiors. Dracula is a fundamentally terrifying figure to be near, and the film stages many of its scenes in small sets, characters forced uncomfortably close to the horrific figure.

If one film stands as the ultimate expression of the Dracula myth, ‘Nosferatu’ is inarguably it. It rises capably above its silent film limitations and manages to be, if not terrifying, surprisingly unsettling. Unfortunate, then, that the next rendition of the story seems to get all the mainstream credit.

Dracula [1931] – Directed by Todd Browning

About a decade later, Hollywood was in the midst of a monster-movie craze and Dracula was ripe for production. With the licensing rights in tow – and therefore no need to utilize the name Nosferatu – ‘Dracula’ is likely the most viewed and remembered version of the Dracula story. Anchored to a famous performance by Bela Lugosi, an at-the-time unknown Bavarian actor, it has done more to ground the Dracula legend in popular culture than any other film.

‘Dracula’ is a different film than ‘Nosferatu’ in countless ways. Aside from some minor changeups to the characters in the story, this version of the tale is far less haunting than the original. While early scenes of the film in Dracula’s castle do their best to match the mood and terror of ‘Nosferatu’, the film quickly changes pace as it moves back to England. It pushes main character Jonathan Harker into the background, instead choosing to emphasize the vampire-hunting doctor Van Helsing. The alteration is strange and ultimately ineffectual, as Van Helsing spends much of the film looking old and feeble, carefully articulating the many manners in which the vampire can be dispatched.

This portion of the film – functionally, its entire second and third acts – take place entirely within the confines of an English drawing room, playing more like a stage play than a film. Unique cinematic touches move the film along, but the pace sags considerably. Lugosi’s take on Dracula is remarkably different from Schrek’s. His vampire is well to-do, cultured, acquainted with modern notions of style and grace. A strip of light is frequently used to focus our attention on his eyes while the rest of his face remains buried in shadow, further enhancing his powers of magic and seduction. Far more than ‘Nosferatu’, this version takes great care to emphasize the character’s ability to impose his will on others. His gaze creates a trance upon those it touches.

Being a sound picture as opposed to the silent ‘Nosferatu’, ‘Dracula’ is able to make use of the soundscape to great effect. Lugosi’s diction is foreign, like the character himself, further adding to his seductive power. While my understanding is that the original film had a minimalist score, the recent re-mastering project carried out a decade ago added a new score composed by Philip Glass and played by the Kronos Quartet. It is absolutely wondrous. It grabbed my attention in every scene, perhaps most especially in the film’s opening act in Dracula’s castle. Purists may argue against its inclusion, but it lends the film an even greater sense of power and dread.

This is ultimately to be the weakest of the four films, though. Lugosi’s Dracula lacks a sense of feral terror; he is, in a sense, almost too well-mannered. His costume and haircut inspire more chuckles than shudders, under-cutting much of the tension. The film is certainly worth seeing for the historical context, but as a “vampire movie”, it is too polite and talkative to really terrify.

Nosferatu the Vampyre [1979] – Directed by Werner Herzog

We jump ahead a half-century, now, to Werner Herzog’s sumptuous remake of the Murnau classic. Making frequent reference to the original film, ‘Nosferatu the Vampyre’ is nonetheless an original and powerful take on the tale.

The iconic role of the vampire – here referred to both as Dracula and Nosferatu, which adds a mythical twist to the character in much the same way that the devil can be referred to as Satan, Beelzebub, etc. – is embodied with startling effectiveness by Klaus Kinski. His makeup and mannerisms echo Schrek’s original performance, and yet his ability to speak aloud offers Kinski the ability to push the character even further. He speaks slowly, carefully, he words well-considered. The addition of a talking vampire admittedly does detract from his vicious appearance in the 1922 film, but it also serves to bring forth Dracula’s more human qualities.

It is often ignored that the tale of Dracula is the tale of a man lost in heartbreak, forced to endure centuries of loneliness. For all the flying bats and gushing blood, his trip to England is predicated on finding a new love for himself, a way to soothe his broken heart. With his careful speech and subtly modulated performance, Kinski makes his Nosferatu into a more sympathetic character than Schrek or Lugosi, a change that is more in line with the original text.

Certain shots are framed identically to the original film, but nonetheless ‘Nosferatu the Vampyre’ has a look all its own. Echoing its time period with considerable grace, it stages a beautiful sequence in which a brace of townspeople, certain of their own mortality from the black plague, sit outside and indulge in the most luxurious meal they can fashion. Made as a joint French and German production, the film has an undeniably foreign feel that creates an overwhelming sense of credibility in the performances and story.

‘Nosferatu the Vampyre’ recasts the original film with a broader palette, its widescreen cinematography doing little to lessen the intimate terror inherent in the story. Its noticeably low budget will occasionally pull you from the experience, but it is perhaps the most subdued and effective portrayal of Dracula as a being for which one she feel terror and sadness in equal measure. It is a wonderful film and it comes highly recommended for those who feel the silent original may be too obtuse for their modern viewing tastes.

Dracula [1992] – Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

Now here’s something different. Inspired by the near-century of films, novels and spinoffs that had been made from the original text, Coppola recasts the story of Dracula as a visually stunning epic melodrama. Filled with massive sets, over-indulgent directing and hammy performances, his ‘Dracula’ is the most fun of the lot.

The titular role is taken up with considerable presence by Gary Oldman. His performance must have been exhausting. He appears in numerous monstrous forms, including that of a werewolf, full-body prosthetics and all. The sadness of the Dracula character is brought intensely to the foreground, the character terrifying in his violent intensity and depressing in his sorrow. The costume design is spectacular. Dracula’s first appearance, with flowing red robes and towering plume of white hair, is unlike any ‘movie monster’ ever filmed. That he proceeds to climb walls and ‘detach’ from his own shadow feels appropriate.

Coppola made much of his attempts to create the film entirely in the old style. There are no modern film effects; everything is done ‘in camera’, with simple and imaginative solutions used instead of CGI. This lends the film something of a timeless feel, despite its casting of then-young stars Keannu Reeves and Winona Ryder.

It is perhaps too long. It is perhaps too extravagant. Neither of these matter much. It tells the tale of Dracula with boundless glee, literally splashing its sets with gallons of blood. People are beheaded, necks are bitten. It’s all good fun, though it obviously tosses terror aside. It is closely adapted from the original text, moreso than any other film, though by removing much of the creepiness it feels as though it has removed some of the point, too.

Just the same, if you’ve never seen a Dracula movie, this is as good a place as any to start. By the time you’ve worked your way back to Murnau’s 1922 original, its all plague rats, sorrow and death. Give Coppola credit for seeing the fun in all this.